Recently I have been trying to wrap my head around what has been happening in the kubernetes runtime space, doing so made me realize that alot has happened and I was too busy to catch up, as a result, I decided to write this blog post which summarizes my thoughts after reading up a bit.

Have a look at this post’s outline and feel free to jump to sections of choice if you already feel confident about the topic.

- A Walk Down the Memory Lane: The Container Wars

- The Open Container Initiative (OCI)

- A Sandbox’s Highs and Lows

- CRIng Out Loud in Kubernetes Land

- CRIng with Gardener

- Summary

- References

A Walk Down the Memory Lane: The Container Wars

History gives us the opportunity to understand our past, which in turns helps us understand our present. In the context of this post, history is less than a decade back, but in the tech industry, a decade is history already. In any case, lets start with 2013 or lets call it “the Docker year”, in my opinion this is where it alllll started.

As you might already know, Docker is not a technology, its what I like to refer to as a “Mashup”, in web terminology, a “Mashup” is :

“A web application that uses content from more than one source to create a single new service displayed in a single graphical interface [1]”

Translation, Docker is simply just a tool-set that brings hard and dark witchcraft that had existed for decades starting from chroot to LMTCTFY [2] to the luxury of our command line with one single command, the almighty docker run. However, one size does not fit all, and staying on the Containers throne just got a lot harder.

Although Docker covered the major part of use-cases, it wasn’t enough, and I won’t go into the details here, but lets say Docker lacked a bit when running under Systemd, had no mechanism for image signing and discovery, had image distribution locked-in,…etc. This triggered a rebellion in that space, mostly from the folks at CoreOS at the time (and others) which led to what we know today as the “Container Wars”.

December 2014, App Container (appc) was announced. Appc, an open specification focused on filling the missing gaps that was not properly addressed by Docker which included an image format, runtime environment, and a discovery protocol. Shortly after in 2015, Docker decided to fight back with new Docker v2.2 image format which as well tried filling out some of the missing gaps.

This continued for a while, until a new body was formed with the aim of bringing this war to an end and bring instead an era of meritocracy-based tech to the container space, this body is known as the Open Container Initiative (OCI), we will be talking more about it in the next sections.

https://kccncna17.sched.com/event/5fa3005107ffa3655968cc44e09fac11

The Open Container Initiative (OCI)

So what is OCI, as always, lets look at definition from the source [3]:

The Open Container Initiative (OCI) is a lightweight, open governance structure (project), formed under the auspices of the Linux Foundation, for the express purpose of creating open industry standards around container formats and runtime. The OCI was launched on June 22nd 2015 by Docker, CoreOS and other leaders in the container industry

As mentioned in the definition, OCI is about creating standards around container formats and runtime, these standards happen to have their own specs, namely the image, runtime and distribution specs. Also if we look for “spec” in the github “opencontainer” project, this is what we will find (ordered chronologically):

So lets take it on one spec at a time.

Image Spec

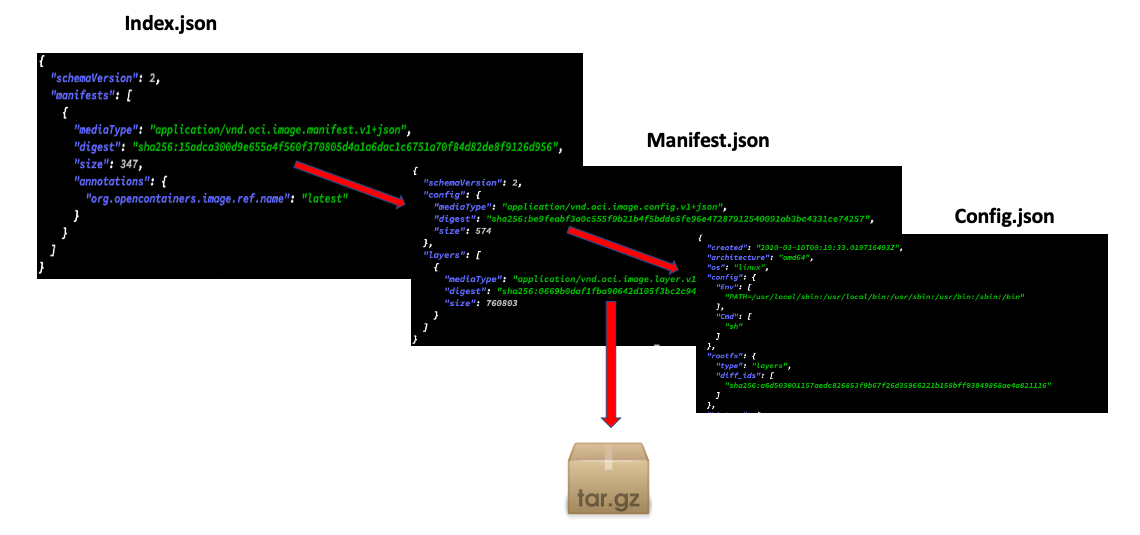

An image spec is nothing but a description of the OCI image tar format. To help you understand, I have an image pulled locally, here is what it contains:

.

|-- blobs

| `-- sha256

| |-- 0669b0daf1fba90642d105f3bc2c94365c5282155a33cc65ac946347a90d90d1

| |-- 15adca300d9e655a4f560f370805d4a1a6dac1c6751a70f84d82de8f9126d956

| `-- be9feabf3a0c555f9b21b4f5bdde5fe96e47287912540091ab3bc4331ce74257

|-- index.json

`-- oci-layout

- The

oci-layoutjust contains the image layout version (e.g., 1.0.0) which serves to provide consistency with the image spec if changes to the layout are made. - The

blobswhich represent the config and the manifest parts of the image spec, as well as the file-system layers.

- The

index.jsonis the entry-point to the whole thing, it points to themanifest.json, which in turns points to the:config.json: contains image configurations that will be later converted to the runtime config file of file system bundle. This bundle will be later fed to the low-level container runtime (more about it later in the post).- The layers of the file-system. The union of these layers will finally represent the container’s

rootfs.

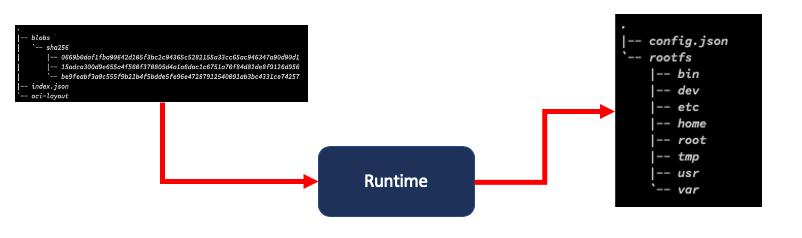

Runtime Spec

The second and most important part of OCI is the runtime-spec. The image-spec did already lay the foundation for what is to come next, this foundation is called the Filesystem Bundle, which is the result of an unpacking process done by the container runtime.

The content of the resulting config.json in the bundle is what defines the entire life-cycle state machine of a container, as well as OS specific config, the processes to run, useful metadata, and most importantly, the path to the container’s rootfs.

A Sandbox’s Highs and Lows

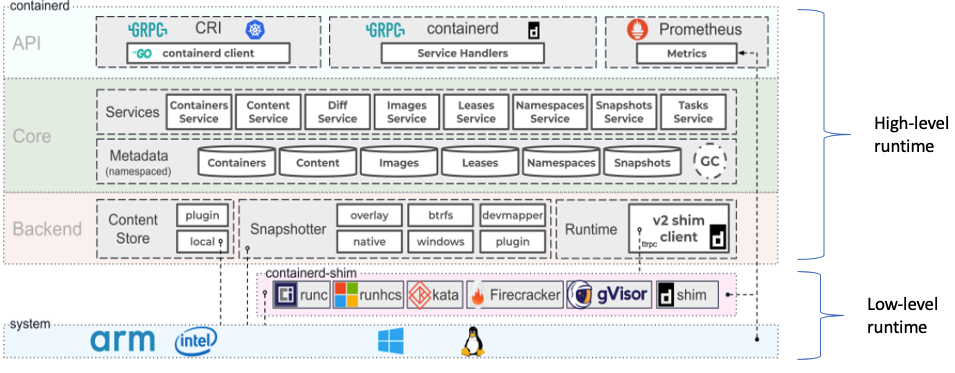

In the previous sections, I might have mentioned the term container-runtime more than once, however, I didn’t really go into the details, therefore, this section will be all about runtimes, in particular high and low level runtimes.

Nowadays when running a container, all that needs to be done is use a tool like Docker to execute a simple command which gets the job done, that might be enough if you are are just an app developer who is just looking for a managed way to run their application, if however “how” this container came to be makes a difference because you are the low-level developer on the other end trying to make it work on different operating systems that have different requirements, then the details of how that container came to be starts to become important.

At the end, it depends on what angle you are looking from, i.e., from high on top (high-level runtime) or from down there where namespaces are getting unshared and cgroups are being forged (low-level runtime).

Examples of high-level runtimes are containerd, cri-o, while examples of low-level runtimes are runc, firecraker, gVisor, kata,..etc) and to get a better idea, here is a comprehensive figure for the containerd architecture as an example that covers both the high and low level aspects of a runtime

As can be seen from the figure, a high-level runtime takes care of tasks such as interfacing with other consumers of the runtime API, image management (pushing, pulling, content-storage, snapshots, diffs, etc.), interfacing with low-level runtimes via the Shim concept (basically a plugin) while the lower-level API is responsible for the plumbing and isolation of namespaces. A low-level runtime needs to implement the shim interface, this way the implementation can differ without changes in the higher-level runtime (e.g., containerd):

service Shim {

rpc State(StateRequest) returns (StateResponse);

rpc Create(CreateTaskRequest) returns (CreateTaskResponse);

rpc Start(StartRequest) returns (StartResponse);

rpc Delete(google.protobuf.Empty) returns (DeleteResponse);

rpc DeleteProcess(DeleteProcessRequest) returns (DeleteResponse);

rpc ListPids(ListPidsRequest) returns (ListPidsResponse);

rpc Pause(google.protobuf.Empty) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

rpc Resume(google.protobuf.Empty) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

rpc Checkpoint(CheckpointTaskRequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

rpc Kill(KillRequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

rpc Exec(ExecProcessRequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

rpc ResizePty(ResizePtyRequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

rpc CloseIO(CloseIORequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

rpc ShimInfo(google.protobuf.Empty) returns (ShimInfoResponse);

rpc Update(UpdateTaskRequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

rpc Wait(WaitRequest) returns (WaitResponse);

}

CRIng Out Loud in Kubernetes Land

Now that we understand the important constituents of runtimes, we can involve Mr. Kubernetes in the game, more specifically the Container Runtime Interface (CRI).

Kubernetes started out as one big blob of code, for simpliciy this helped kubernetes make a name fast as a container orchestrator that does what it should well. However, it was very hard to extend since extensibility just meant growing the in-tree code to provide additional features be it in networking, storage, runtimes, etc.

For a long time, Kubernetes had only Docker as its go-to container runtime, but with the developement of other runtimes, the gravity towards Docker started to fade out, and there was a growing interest from vendors to support other container runtimes. As they say need is the mother of invention, in this case the child / invention was CRI.

Similar to what happened with OCI, the community developed a standard interface for communicating with container runtimes (high-level runtimes). Want to be exposed in Kubernetes as a supported runtime? Implement the interface, as simple as that. So how does this interface look like? Here is a sample from the Kubernetes blog [4]:

service RuntimeService {

// Sandbox operations.

rpc RunPodSandbox(RunPodSandboxRequest) returns (RunPodSandboxResponse) {}

rpc StopPodSandbox(StopPodSandboxRequest) returns (StopPodSandboxResponse) {}

rpc RemovePodSandbox(RemovePodSandboxRequest) returns (RemovePodSandboxResponse) {}

rpc PodSandboxStatus(PodSandboxStatusRequest) returns (PodSandboxStatusResponse) {}

rpc ListPodSandbox(ListPodSandboxRequest) returns (ListPodSandboxResponse) {}

// Container operations.

rpc CreateContainer(CreateContainerRequest) returns (CreateContainerResponse) {}

rpc StartContainer(StartContainerRequest) returns (StartContainerResponse) {}

rpc StopContainer(StopContainerRequest) returns (StopContainerResponse) {}

rpc RemoveContainer(RemoveContainerRequest) returns (RemoveContainerResponse) {}

rpc ListContainers(ListContainersRequest) returns (ListContainersResponse) {}

rpc ContainerStatus(ContainerStatusRequest) returns (ContainerStatusResponse) {}

...

}

service ImageService {

rpc ListImages(ListImageRequest) returns (ListImageResponse) {}

rpc ImageStatus(ImageStatusRequest) returns (ImageStatusResponse)

rpc PullImage(PullImageRequest) returns (PullImageResponse) {}

rpc RemoveImage(RemoveImageRequest) returns (RemoveImageResponse) {}

rpc ImageFsInfo(ImageFsInfoRequest) returns (ImageFsInfoResponse) {}

}

As can be seen from the interfaces above, there are two service interfaces, namely RuntimeService and ImageService, where both define main functions that should be implemented by the higher-level runtime interfacing with a container runtime client, in this case its Kubernetes. Both service interfaces should respect and talk OCI, and be able to relay requests to lower-level runtimes to do the actual work of assembling containers.

Kubernetes supports many high-level container runtimes, prominent examples are Docker, CRI-O, Containerd, Frakti, etc.

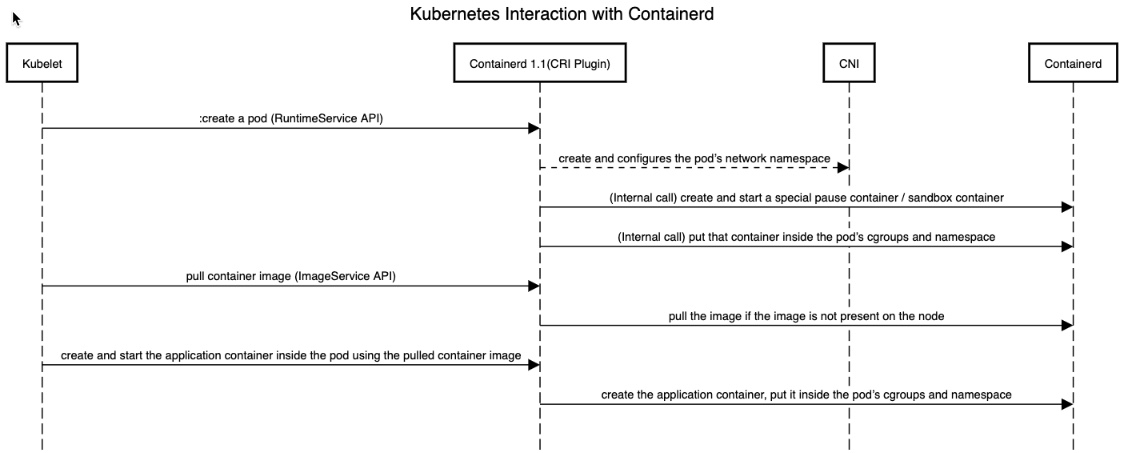

Before we dig into the details of the “How”, lets look at the “Who”. When I say kubernetes uses CRI, I am being a bit too generic, the component that is really involved in CRI communication is our dear fellow Kubelet. The Kubelet is the kubernetes entity that handles requests coming from the API server to create, update, delete pods / volumes (pod life-cycle) as well as requests for sub-resources (e.g., logs, port-forward). After receiving these requests, the Kubelet itself acts as a client and uses the CRI interface to call out the container-runtime to actualize the request. Find below a sample flow assuming we are to use Containerd as our runtime interface:

Configuring CRI

So now that we understand a bit about the flow, how do we configure the kubelet to use the right container-runtime, and more, how do choose what runtime we want. Again, we will show as example how to configure containerd as the high-level container runtime.

First step is to configure the kubelet with the following flags:

# The container runtime to use. Possible values: 'docker', 'remote', 'rkt(deprecated)'. (default "docker")

--container-runtime=remote

# The endpoint of remote runtime service. Currently unix socket endpoint is supported on Linux, while npipe and tcp endpoints are supported on windows.

--container-runtime-endpoint=unix:///run/containerd/containerd.sock

In our case we are choosing remote as the value for the container runtime, and we are pointing the requests to the containerd unix socket. Next step, is to configure the low level runtime.

Once containerd is installed (after a bunch of apt-gets and curls [5]), the following command can be executed to get a default containerd configuration file:

containerd config default > /etc/containerd/config.toml

The resultant config would be a long file, with the following lines being the most important in choosing the low-level runtime:

# 'plugins."io.containerd.grpc.v1.cri".containerd' contains config related to containerd

[plugins."io.containerd.grpc.v1.cri".containerd]

# snapshotter is the snapshotter used by containerd.

snapshotter = "overlayfs"

# no_pivot disables pivot-root (linux only), required when running a container in a RamDisk with runc.

# This only works for runtime type "io.containerd.runtime.v1.linux".

no_pivot = false

# default_runtime_name is the default runtime name to use.

default_runtime_name = "runc"

In the above config, the default runtime is runc, so with no effort we get a running containerd daemon talking to runc to run containers. All good, but what if we want to switch to another low-level runtime? well no biggie, we use a RuntimeClass :)

The RuntimeClass

If we just want to run containers, do we really care about low-level runtimes? No we just want kubectl run --name fire-me-up-i-dont-care and we get a container. If you really just want to do that, you can stop reading now, and I apologize for wasting your time. IF however, you care about low-level runtimes, for example, if security is a major concern then you might be thinking “runc is not that secure, I want to enable gVisor to get cutting edge payload isolation”, then its your lucky day for we have Runtime classes to just do that.

Runtime classes is CRI’s way to provide runtime alternatives to choose from when running a pod. For example, consider the following runtime classes configured in the cluster [7]:

kind: RuntimeClass

apiVersion: node.k8s.io/v1alpha1

metadata:

name: native # equivalent to 'legacy' for now

spec:

runtimeHandler: runc

---

kind: RuntimeClass

apiVersion: node.k8s.io/v1alpha1

metadata:

name: gvisor

spec:

runtimeHandler: gvisor

----

kind: RuntimeClass

apiVersion: node.k8s.io/v1alpha1

metadata:

name: kata-containers

spec:

runtimeHandler: kata-containers

Each RuntimeClass has a runtimeHandler which correspond to the low-level runtime to use if this runtime class is to be chosen. Running a pod with gVisor is a matter of modifying the pod spec and adding a runtimeClassName as follows:

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: gVisor-nginx

spec:

replicas: 2

selector:

matchLabels:

app: gVisor-nginx

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: gVisor-nginx

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: gVisor

spec:

runtimeClassName: gVisor

Similarly I can choose from the other available runtime classes and run the pod with kata-containers for example.

CRIng with Gardener

Okay now we know how to configure and use different container runtimes, this however can be so much work everytime a new cluster is spawned, so the question now is… “can I as a user, just configure my cluster to use a different container runtime with a one-liner?” and the answer is YES. There are many managed kubernetes services out there but only a handeful come with a one-line configuration for different container runtimes, one of these is Gardener.

In Gardener, a Kubernetes cluster is called a Shoot (in case you are wondering about the name, check this out). To configure a container runtime for the cluster worker nodes, all we need to do is:

workers:

- name: cpu-worker

cri:

name: containerd

containerRuntimes:

- type: gvisor

The one liner is the type in the spec, once this is done, Gardener takes care of installing all the binaries, config, runtime classes, … and everything that is needed to get your cluster up and running with gVisor in this case.

The full example of a Shoot can be found here. Furthermore, Daniel Foehr, a colleague of mine gave a great talk on how different container runtimes can be enabled in Gardener, so if you are curious check his talk out here.

Summary

Alrighttt, we are finally in the end of this post, so what did we talk about? First we had a look at the history of containers, and how different requirements for addressing and distributing images led to common standards such as Appc and OCI that enabled extensibility and choice in the container space. Then we dug a little deeper into OCI and examined the different specs to use, namely the Image and Runtime specs.

Next, we explained the difference between high and low level container runtimes, and how they are configured and used in Kubernetes using yet another standard interface called the Container Runtime Interface (CRI) that helped remove in-tree runtime specific code from Kubernetes and introduced the concept of runtime extensibility that led to yet more choice.

Finally, we had a look at one example of managed kubernetes services (e.g., Gardener) and how trivial it is to configure and use different container runtimes.

I hope this post was helpful to you in anyway, if you have any feedback please let me know.

Thanks for tunning in :)

References

- [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mashup_(web_application_hybrid)

- [2] https://github.com/google/lmctfy

- [3] https://www.opencontainers.org/about

- [4] https://kubernetes.io/blog/2016/12/container-runtime-interface-cri-in-kubernetes/

- [5] https://kubernetes.io/docs/setup/production-environment/container-runtimes/#install-containerd

- [6] https://github.com/google/gvisor

- [7] https://github.com/kubernetes/enhancements/blob/master/keps/sig-node/runtime-class.md

- [8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shoot