I Vibe-coded an open registry for AI agents

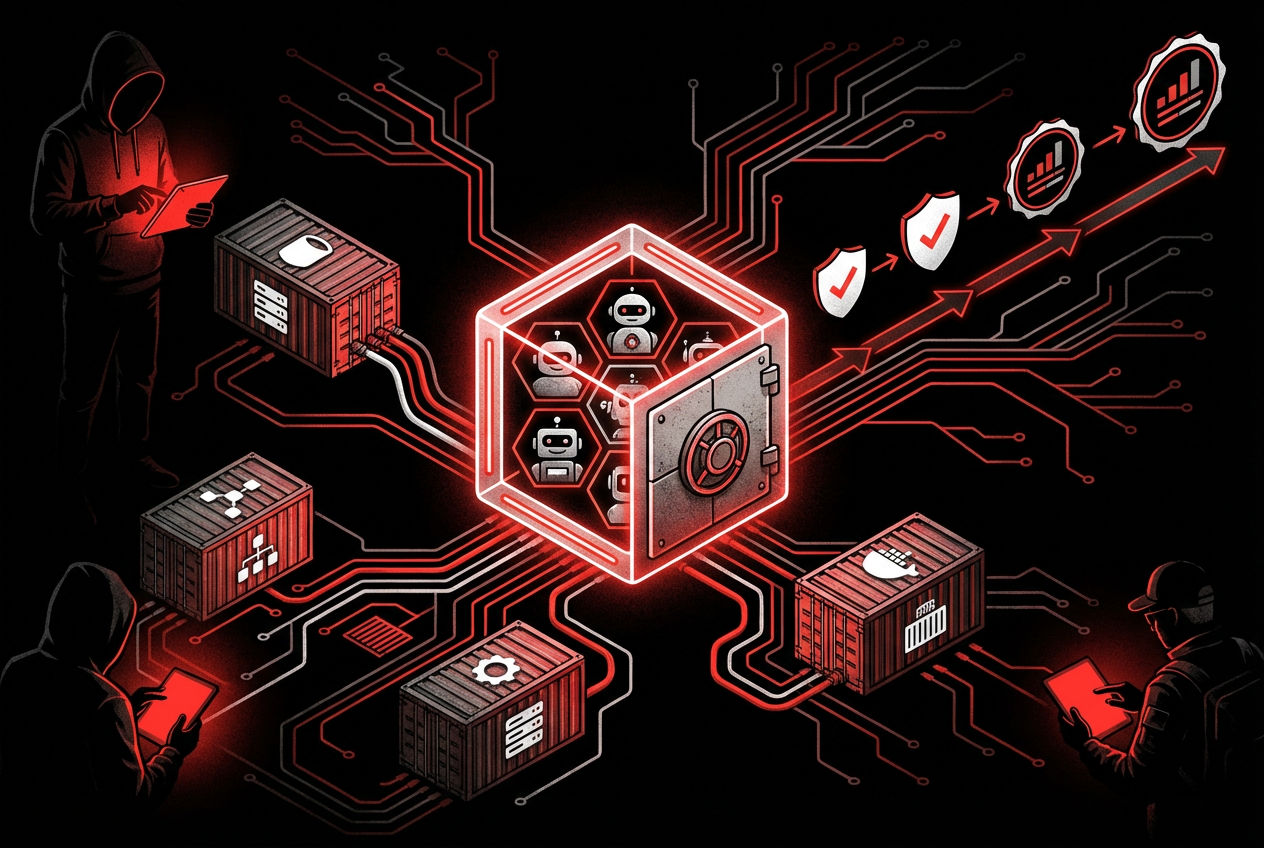

There’s a weird gap in the AI tooling ecosystem right now. We can build agents, deploy them in containers, connect them to MCP servers, give them skills and tools. But ask a basic question: “What models does this agent use? Has anyone evaluated it for safety? What MCP servers does it call? Who approved it for production?” and you get blank stares.

Container registries store bytes. They don’t know what’s inside. An OCI image tagged my-agent:v2.1 could use GPT-4o or a fine-tuned Llama, could call six MCP servers or none, could have been red-teamed or just vibed into production on a Friday afternoon. The registry doesn’t care. It stores layers and digests.

This felt like a problem worth solving.

Agents are containers with weird dependencies

Strip away the hype and an AI agent is an application. It runs in a container. It has a process, memory, a network port. You build it, push it to a registry, deploy it on Kubernetes. From an infrastructure perspective, it’s a workload like any other.

But the dependencies are unlike anything we’ve managed before.

A traditional microservice depends on libraries, databases, maybe an external API. You pin versions, you run CVE scans, you track the supply chain with SBOMs. Boring, well-understood, solved.

An AI agent depends on a model. That model is probabilistic. The same input can produce different outputs. Research measuring hallucination rates shows rates ranging from 3% on text summarization to over 90% on specialized tasks like legal citation generation. Industry reports indicate financial losses exceeding $250M annually from hallucination-related incidents. A UK police chief stepped down after an investigation was compromised by a Copilot hallucination.

And it gets worse when agents compose. Galileo’s research on multi-agent coordination found that boundary issues become particularly problematic in systems with adaptive agents. As agents expand or contract their perceived responsibilities, the boundaries between them shift unpredictably, creating inconsistent coverage that leads to hallucinations nobody anticipated.

The agent also depends on MCP servers, which are themselves services with their own dependencies and failure modes. And on skills, which are prompt bundles that may reference other skills. And on specific model providers, which may change pricing, deprecate versions, or alter behavior without warning.

So you have a container, sure. But the container’s behavior depends on a probability distribution, a chain of external tool servers, and prompt templates that may or may not work the same way after the model provider ships a new version on Tuesday.

Jimmy Song wrote that agents are evolving from tools into distributed systems, and single-agent designs resemble early monoliths: impressive demos, fragile behavior, opaque failure modes. Deloitte found that only 11% of organizations are actually running agents in production. 42% are still developing their strategy. The gap between “look at this demo” and “this runs in prod” has never been wider.

Traditional infrastructure tooling doesn’t capture any of this. Your container registry doesn’t know which model your agent calls. Your SBOM doesn’t list prompt templates. Your CI pipeline doesn’t track whether anyone ran a red-team evaluation before the last deploy.

That’s the gap.

The actual problem

I kept running into the same situation: teams building agents internally, deploying them, and then losing track of what depends on what. An agent uses a Kubernetes MCP server for cluster access. That MCP server gets updated. Did anyone check if the agent still works? Who knows, because nobody recorded that dependency.

The MCP ecosystem is growing fast. The official MCP Registry launched in preview in September 2025, and there are now 1,000+ servers in the community registry. Docker has an MCP catalog. GitHub has one too. Kong announced an enterprise MCP registry in February 2026.

But these registries focus on MCP server discovery. They answer “what MCP servers exist?” They don’t answer “what does this agent depend on, has it been evaluated, and is it safe to run in production?”

Microsoft’s Agent Registry in Copilot is interesting but locked to their ecosystem. Google’s Cloud API Registry integration in Vertex AI Agent Builder does something similar for their platform.

Nothing is vendor-neutral. Nothing works across frameworks. Nothing tracks the full supply chain of an agent: its models, its tools, its skills, its evaluation history, its promotion through a governance lifecycle.

What I built

The Agent Registry is a metadata store that sits alongside OCI registries. It doesn’t store containers or binaries. It stores structured metadata about three types of AI artifacts:

- Agents: autonomous AI systems with container runtimes, model dependencies, and tool integrations

- Skills: reusable prompt-based capability bundles (no runtime, think playbooks)

- MCP servers: Model Context Protocol servers that expose tools and resources

Each artifact gets a YAML manifest describing what it is, what it depends on, and how it’s been evaluated. The registry stores that metadata and provides an API for discovery, evaluation, and governance.

It works with any agent framework. LangChain, CrewAI, ADK, Llama Stack, custom builds. The registry doesn’t care how you built the agent. It cares what the agent uses and whether anyone has checked if it’s safe.

The Bill of Materials

This is the part I think matters most. Every agent declares a Bill of Materials (BOM) that lists:

- What models it uses (and which provider, and what role: primary vs. fallback)

- What MCP servers it calls (with version constraints)

- What skills it composes

- What prompts it ships with (hashed for integrity)

You can resolve the full dependency tree with a single command:

agentctl deps agents acme/cluster-doctor 1.0.0agent acme/cluster-doctor@1.0.0

|- model granite-3.1-8b-instruct@ibm [resolved]

|- model llama-3.1-70b-instruct@meta [resolved]

|- mcp-server acme/kubernetes-mcp@>=2.0.0 [resolved]

|- mcp-server acme/prometheus-mcp@>=1.0.0 [resolved]

|- skill acme/k8s-troubleshooting@>=1.0.0 [resolved]This is what CoSAI has been calling for with AI SBOMs. The difference is I built the tooling that actually does it.

Evaluation records

The registry accepts evaluation results from external tools. It doesn’t run evaluations itself. Garak runs a toxicity scan? The registry stores the result. Eval-hub runs a benchmark? Same. A human reviewer signs off? That goes in too.

agentctl eval attach agents acme/cluster-doctor 1.0.0 \

--category safety --provider garak \

--benchmark toxicity-detection --score 0.96Categories include safety, red-team, functional, and performance. Each record captures the provider, benchmark, score, evaluator identity, and method (automated, human, or hybrid).

McKinsey reported that 80% of organizations have already encountered risky behaviors from AI agents, including improper data exposure and unauthorized access. Having evaluation records attached to the artifact itself, not buried in a CI log somewhere, seems like the minimum bar.

Promotion lifecycle

Artifacts move through a governance lifecycle: draft, evaluated, approved, published, deprecated, archived. Each transition is gated and recorded.

draft --> evaluated --> approved --> published --> deprecated --> archivedMoving to evaluated requires at least one eval record. Content becomes immutable after that point. What was tested is what gets shipped. No sneaking in changes after the safety review.

Every promotion step records who did it, when, and why:

agentctl inspect agents acme/cluster-doctor 1.0.0agent acme/cluster-doctor@1.0.0

Status: published

Published: 2026-02-21T10:40:36Z

Eval Records: 3

safety 1 record(s)

red-team 1 record(s)

functional 1 record(s)

Average score: 0.92

Promotion History:

draft -> evaluated -- All evals pass

evaluated -> approved -- Reviewed by platform team

approved -> published -- Production-readyThe CLI and server

There are two entry points. agentctl is the CLI for pushing artifacts, running queries, and managing the registry. A separate server binary handles the HTTP API and embedded web UI. For local development, agentctl server start runs both in one process. For production, the server binary is what goes in the container.

# Local dev

go build -o agentctl ./cmd/agentctl

./agentctl server start

# Production container builds cmd/server

make image push deployThe CLI also has an init command that scans your project source code with an LLM and generates the manifest for you. Point it at a directory with a Dockerfile, some Python or Go code, and a README, and it figures out the kind (agent, skill, or MCP server), extracts dependencies, and writes the YAML. Works with Anthropic, OpenAI, Ollama, vLLM, or any compatible endpoint.

agentctl init --path ./my-agent --image ghcr.io/acme/my-agent:1.0.0 -o manifest.yamlDeployed on OpenShift

The registry runs on Kubernetes and OpenShift. I have a multi-stage Dockerfile, Kustomize overlays for both vanilla k8s and OpenShift, and a Makefile that does build, image, push, deploy in four commands.

make image push deployThe server uses SQLite for storage (swappable to Postgres), embeds a web UI, and runs as non-root with a read-only root filesystem. Passes OpenShift’s restricted SCC without any grants.

How this compares to agentregistry-dev

There’s an existing project called agentregistry that solves a related but different problem. It’s a runtime deployment system: you give it MCP servers, skills, and agents, and it manages running instances via Docker Compose and a reverse proxy gateway. It answers “how do I run these things locally?”

My project answers a different question: “how do I govern, version, and trust these things across environments?” The agentregistry-dev project has basic published/unpublished states but no formal promotion lifecycle, no evaluation record schema, and no transitive BOM resolution. It does have useful enrichment (GitHub stars, security scanning via OpenSSF Scorecard), but governance metadata lives outside the artifact.

They’re complementary. You could use agentregistry-dev to deploy locally and my registry to track what’s been evaluated, approved, and published for production. Different layers of the same problem.

Why this matters now

A Gartner analyst noted that MCP’s authentication and authorization model is limited. Tray.ai coined the term “Shadow MCP” for the growing problem of unmanaged MCP servers in enterprises. Tetrate wrote about securing the MCP supply chain as an infrastructure concern.

On Reddit, an MIT researcher posted in r/artificial asking “who’s actually feeling the chaos of multiple AI agents working together?” The responses were telling: coordination, compliance, and trust were the top pain points. In r/devops, “would you trust an AI agent in your cloud environment?” got mostly skeptical responses. In r/kubernetes, someone built an AI SRE, realized LLMs are terrible at infra, and rewrote it as a deterministic linter.

The pattern is clear: people are building agents, hitting trust and governance walls, and then either giving up or bolting on ad-hoc solutions. There’s no standard way to say “this agent has been safety-tested, here’s the proof, and here’s everything it depends on.”

That’s the gap I’m filling.

The bigger picture

Gartner expects 40% of enterprise applications to have task-specific agents built in by 2026, up from under 5% in 2025. Predictions suggest agentic AI will represent 10-15% of IT spending in 2026. But Gartner also predicts that over 40% of agentic AI projects will fail by 2027 because legacy systems can’t support modern AI execution demands.

The organizations that figure this out will be the ones that treat agents like what they are: applications with model dependencies and unpredictable behavior that need the same (or stricter) governance as any production service. Not magic. Not demos. Infrastructure.

OpenAI’s September 2025 research definitively showed that standard training procedures reward guessing over acknowledging uncertainty. Your agent would rather hallucinate an answer than say “I don’t know.” That’s a feature of the model, not a bug you can patch. The only defense is governance: evaluation before deployment, immutability after approval, and a clear record of what was tested.

Or as one r/kubernetes commenter put it: “the k8s community doesn’t hate AI agents. They hate deploying things they can’t reason about.” Fair enough. The Agent Registry is my attempt to make agents something you can reason about.

What’s in the repo

The agent-registry repo includes:

- Full Go implementation (CLI + server + embedded web UI)

- 8 JSON schemas (draft 2020-12) for all artifact types

- OpenAPI 3.1 REST API spec

- Dockerfile + Kustomize manifests for k8s and OpenShift

- Example manifests for agents, skills, and MCP servers

- Presentation deck covering the problem and architecture

The spec covers 12 sections including the data model, BOM structure, version model, promotion lifecycle, OCI integration, eval results, provenance (SLSA, Sigstore, SBOM), trust signals, access control, and federation between registry instances.

It’s Apache-2.0 licensed and works with any agent framework.

Try it

git clone https://github.com/agentoperations/agent-registry

cd agent-registry

make build

./bin/agent-registry # starts server on :8080Or deploy to your cluster:

make image push deployThis is an experiment. I’m figuring out what the right abstractions are for governing AI artifacts. If you’re dealing with similar problems, I’d like to hear about it.

The Agent Registry is an agentoperations project.