In this post we will be covering eBPF concepts, as well as challenges faced when applying network policies for microservices and how these challenges can be tackled. Finally, we will have a look at Cilium to see how it makes eBPF simple and easy to utilize.

- Introduction - What is eBPF - The bpf() system call - Important use-cases for eBPF - How to create an eBPF program?

- Microservices - What are Microservices and how do they work? - Security policies with IPTables - Security Policies using eBPF

- Cilium - Cillium Important Concepts - Important Cilium Constructs - Cilium Policies - Demo

- Important References

Introduction

In this section we are going to answer some important questions as:

- What is BPF and eBPF? What is difference between them?

- Use-cases for eBPF

- What is the eBPF system call and why is it important?

- How to create an eBPF program?

What is eBPF

Before talking about extended Berkely Packet Filters (eBPF), lets remove the ‘e’ for a second and talk about BPF.

BPF was first introduced in 1992 by Steven McCanne and Van Jacobson as an in-kernel virtual machine that translates byte-code to the underlying machine-architecture and provides packet filtering using a simple instruction set on Free-BSD and Linux. Before the introduction of BPF, packet filtering APIs such as Sun’s STREAMS NIT, DEC’s Ultrix Packet Filter, SGI’s Snoop and Xerox Alto had CMU/Stanford Packet Filter had to copy packets from the kernel to the userspace to be filtered, needless to say, it is not a the most optimal way to do line-rate packet filtering especially when traffic peaks. Also, copying all packets into userspace is expensive.

To filter packets with BPF, fitler-expressions (e.g., “ip or tcp and port 80”) were defined, then parsed to produce byte-code. The byte code would then be attached to a tap interface and is then injected into the kernel in the form of native instructions after being checked by a verifier (makes sure that the program terminates and is safe to execute).

Basically, if you have used tcpdump then you have made use of BPF, the filter that you specify will be compiled to BPF byte code, then inserted into the kernel showing only the packets that applies to that filter.

Now, let’s put the ‘e’ back on, so what is eBPF?

With BPF, we are pretty much limited to packet fitlering and monitoring, therefore BPF was extended to do much more (e.g., parsing, lookup, update, modification), hence the name extended BPF (eBPF). Below are some of the features that were introduced with eBPF:

- A separate system call which is externally usable with BPF:

int bpf(int cmd, union bpf_attr *attr, unsigned int size)

- The eBPF system call is a combination of the following functions:

- BPF map functions: Create, iterate, lookup

- BPF load function: Load eBPF program

- Attach maps to eBPF programs

- 64-bit vs 32-bit registers in classical BPF

- Added support for more registers (10 instead of 2 in classic BPF).

- Secure access to kernel memory through kernel getter functions.

- Faster interpretation and Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation.

- State persistance across events through BPF Maps (global data-store) which allows for collecting statistics and enabling context-aware behavior between kernel and userspace. To create a map, the following call is done:

bpf(BPF_MAP_CREATE, union bpf_attr *attr, u32 size) - Helper functions within the kernel (e.g., RNG, timestamps):

- map_lookup/update/delete

- ktime_get

- packet_write

- fetch

- Tail calls that can stitch together multiple bpf programs (passing along context/packets)

A feature-based comparison can be found in the table below:

The bpf() system call

When the eBPF functionality was added as of version 3.18 of the kernel, two features were the key enablers:

- The bpf() system call

- The underlying kernel magic.

The bpf system call can be showed below:

// From the macro expansion of the following code:

// int bpf(int cmd, union bpf_attr *attr, unsigned int size);

int bpf(int cmd, union bpf_attr *attr, unsigned int size);

Lets look at these paramters in details

- The

cmdparameters is basically telling the kernel which command to execute. There are ten availabe commands that can be passed for this parameter:

// From https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v4.11/include/uapi/linux/bpf.h#L73

enum bpf_cmd {

BPF_MAP_CREATE,

BPF_MAP_LOOKUP_ELEM,

BPF_MAP_UPDATE_ELEM,

BPF_MAP_DELETE_ELEM,

BPF_MAP_GET_NEXT_KEY,

BPF_PROG_LOAD,

BPF_OBJ_PIN,

BPF_OBJ_GET,

BPF_PROG_ATTACH,

BPF_PROG_DETACH,

};

- The

bpf_attris a pointer to union which can allow different structs to be passed to thebpfcall. The available structs can be found in here, but lets point them out below:

union bpf_attr {

struct { /* anonymous struct used by BPF_MAP_CREATE command */

__u32 map_type; /* one of enum bpf_map_type */

__u32 key_size; /* size of key in bytes */

__u32 value_size; /* size of value in bytes */

__u32 max_entries; /* max number of entries in a map */

__u32 map_flags; /* prealloc or not */

};

struct { /* anonymous struct used by BPF_MAP_*_ELEM commands */

__u32 map_fd;

__aligned_u64 key;

union {

__aligned_u64 value;

__aligned_u64 next_key;

};

__u64 flags;

};

struct { /* anonymous struct used by BPF_PROG_LOAD command */

__u32 prog_type; /* one of enum bpf_prog_type */

__u32 insn_cnt;

__aligned_u64 insns;

__aligned_u64 license;

__u32 log_level; /* verbosity level of verifier */

__u32 log_size; /* size of user buffer */

__aligned_u64 log_buf; /* user supplied buffer */

__u32 kern_version; /* checked when prog_type=kprobe */

};

struct { /* anonymous struct used by BPF_OBJ_* commands */

__aligned_u64 pathname;

__u32 bpf_fd;

};

struct { /* anonymous struct used by BPF_PROG_ATTACH/DETACH commands */

__u32 target_fd; /* container object to attach to */

__u32 attach_bpf_fd; /* eBPF program to attach */

__u32 attach_type;

__u32 attach_flags;

};

} __attribute__((aligned(8)));

- different BPF program types can be loaded, as sepcified in the

bpf_prog_typestruct:

enum bpf_prog_type {

BPF_PROG_TYPE_UNSPEC,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_SOCKET_FILTER,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_KPROBE,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_SCHED_CLS,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_SCHED_ACT,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_TRACEPOINT,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_XDP,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_PERF_EVENT,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_CGROUP_SKB,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_CGROUP_SOCK,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_LWT_IN,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_LWT_OUT,

BPF_PROG_TYPE_LWT_XMIT,

};

- finally, the size passed in the system call is the size of the struct passed for the

bpf_attr.

Important use-cases for eBPF

eBPF enables important use-cases for different themes:

- Networking (e.g., traffic-control, actions for flow hits/miss, packet parsering and manipulation)

- Tracing (kprobes, uprobes, tracepoints, …)

- Hardware Modeling (e.g., p4)

- Own datapath (which is an important use-case for microservices).

How to create an eBPF program?

There are two ways to write an eBFP program:

- if you are one of those machine-men who like writing byte code, you can definitely do that (may the odds be ever in your favor).

- Use backend-conversion tools like LLVM and write your program in a higher-level language (e.g, C) which then gets compiled to byte code.

After that the byte code is verified, compiled with a JIT compiler to the CPU arhitecture at hand, and finally injected at the desired hook point (e.g., at the traffic control layer). This way policies on packets can be enforced even before being processed the network stack.

Microservices

Now that we understand how eBPF works, lets look into some constructs we will need for having the necessary knoweldge building blocks. In this section, we are going to:

- Understand how microservices interface with the outside world and with one another

- Look at how security policies are currently applied to microservices.

- Look at how security polies would work with eBPF

What are Microservices and how do they work?

If you have been following the posts on my blog, I have previously discussed the definition of microservices and how you can decompose a monoltih into microservices.

But to recap, a microservice is an architecture style for building applications so that they are more loosely coupled, easy to modify, test, and integrate with other microservices. The separation of concerns gives you additional felxibility to scale,test, and deploy your appliations independently from one another.

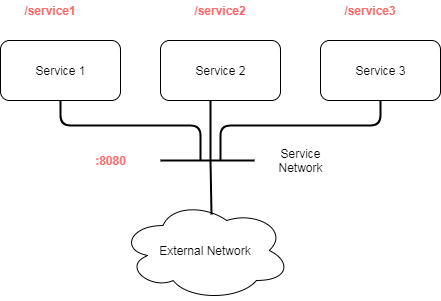

Usually, to successfully apply the microservice model of developement, each service should do one thing and do it well. Furthermore, most of the microservices nowadays are based on HTTP, whereas each service interfaces with the outside world by exposing a path to the service it offers. For example, consider the below figure, where we have three microservices, each exposes a different path.

Since each microservice exposes a different path, and maybe even a different port, the question arises as to how can we apply security polocies to such services.

Security policies with IPTables

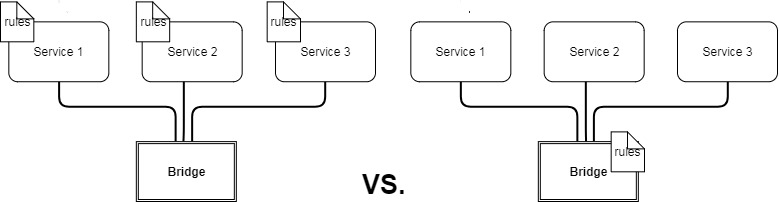

There are two methods to apply security policies with IPTables:

- Define rules customized for every container / microservice

- Define rules on a more granualr level on the bridge that connects the services together (speaking of in-host networking here)

If we are talking about microservices and how many they can be on single host, we can safely assume that its not going to be a walk in the park setting these rules up on a per-container level, needless to say, it is not so easy to scale. Therefore, in a container run-time such as docker, this is how security policies and NAT rules are applied. Alternatively, with OpenStack for example, network namespaces are used to carry out the routing functionality and therefore carry its own IPTable rules configuration.

Now that we know how IPTables rules are applied, there are two things that are yet left to discuss.

What happens when IPTables are used in a microservice architecure?

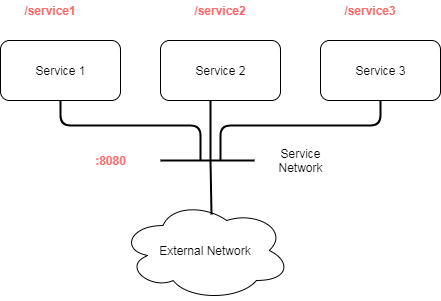

To answer the first question, lets revisit a sample microservice application architecture through the figure below:

With IPTables, we can do things such as accepting or dropping packets/segments based on their L3/L4 parameters.

What if we want to apply security policies based on the application level verbs (e.g., with REST GET/PUT/POST/DELETE) or RPC Paths (/service1, /service2, /service3) for each microservice? With IPTables, we can apply policies for instance, only to allow packets with destination port of 8080, but not application level policies on a per-path level.

How efficient it is to use IPTables for microservices? To answer this questions, lets look at what happens when a packet is sent from a container that represents a microservice.

Each container (network namespace) has its own stack. Therefore, the steps that will be followed are:

- The client program will issue a

connect()system call - The packet will be path through the stack and get constructed accordingly.

- The packet will be forwarded out of the namespace through a vETH pair.

- The host will recieve the packet, apply IPTables rules and decide whether to drop or forward the packet to destination.

- Finally, the client is notified in case the packet is dropped with a RST message.

In terms of hops, we need 5 hops of calls to reach to a decision on whether that particular packet should be forwarded which is not the most optimum scenario. Can we do better? Let’s have a look at eBPF policies.

Security Policies using eBPF

So IPTables are not the best solution for applying policies to microservices as they are limited to L3/4 policies, furthermore, they need whole packet construction and forwarding to reach to a decision.

With eBPF we really don’t need to go all the way in constructing the packet. eBPF programs hook into the kernel, which makes it possible to apply policies on the system call level before even entering the stack or constructing a packet. eBPF attaches to the container network namespace, as a result, all the calls are intercepted and filtered on the spot.

eBPF also has a feature called maps which allows infromation sharing between different BPF programs or between userspace and kernel-space. One application for such feature is sharing state between containers and proxy services.

- Packet is intercepted by a BPF program.

- Oiriginal destination is stored in a map, current destination becomes the proxy.

- Proxy recieves the packet, looks at the shared state, determines whether it is okay to forward the packet to destination or not.

- if allowed, re-inject packet to destination container network namespace.

- if not, drop packet and notify sender.

So far we have been talking about the technologies but we have not really discussed the tools or frameworks that unlocks the ease-of-use for configuring such policies (you guessed right, I am talking about Cillium).

Cilium

So far so good, lets review what we have in our knowledge pocket so far.

- We know what eBPF is.

- We know how to apply policies with eBPF.

- We also know that security policies for microservices are. better applied with eBPF policies than with IPTable rules.

Cillium Important Concepts

Since the documentation on the main page of the Cillium project is quite good,I am not going to repeat whats there, I will rather summarize the important bits, you can have a look yourself here.

Copied from the documentation, the Cilium definition is:

Cilium is open source software for transparently securing the network connectivity between application services deployed using Linux container management platforms like Docker and Kubernetes.

- To me, Cilium is to BPF as Docker is to namespaces, CGroups, UnionFS,…

- It abstracts the creation of policies from the heavy-lifting required to do it.

- Policies are applied and updated without any changes in application code or container config.

What we are really interested in though is how Cilium applies security policies, but before that lets have a look at two important constructs.

Important Cilium Constructs

-

Endpoint - One or more containers that share the same address and namespace (e.g., -c containers Docker and Pods in K8s)

-

Labels - endpoints are assigned labels from container runtime (Docker metadata or pod labels in k8s) Used for applying policies Labels are prefexed with container: for Docker and k8s: for kubernetes (e.g., k8s:id=app1)

Cilium Policies

Cilium can enforce security policies in different ways:

-

Identity based Connectivity Access Control: These are mainly L3 policies that dictates which endpoints can communicate based on their assigned label.

-

Port Restrictions: This is a layer L4 policy that restricts which ports application can use to communicate.

-

Application Level Access Control: enforces L7 access control based on protocol calls (e.g., RPC or REST CRUD).

Demo

Please find below a scripted demo, which follows the instruction on the project documentation page to show how policies can be applied with Cilium along with Docker.

Important References

- Affan A. Syed - eBPF and IO Visor: The What, how, and what next!

- Thomas Graf - Cilium: Network and Application Security with BPF and XDP